We about to get legal up in this bitch; so if you don’t fancy brain strain and big words, this ain’t the post for you. May I suggest skipping to the next Booze post? There’s a really tasty tequila cocktail waiting for you.

While unnecessary, I feel the need to disclaim this opinion piece by saying I’m not a constitutional law attorney. I’m a contract kid. But, statutes are a huge part of my practice and are interpreted in a similar fashion to contracts, so I figure with about 10 years under my belt, I picked up a thing or two about how to juggle statutory interpretation and case precedent, which is kind of all this is.

If you’re not up on the news, the Supreme Court recently ruled against Harvard University and University of North Carolina, finding the schools’ admission programs violated the Equal Protections Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Specifically, the Supreme Court found the schools’ attempts to diversify their student population did not pass the strict scrutiny standard of review necessary to impose race-based restrictions on admissions.

The media refers to this case as the “Affirmative Action” case, and everyone’s up in a tuss about it.

I’m going to treat this blog post as a legal memorandum, so there’s gonna be subsections up in this bitch.

I. What the Fuck is Affirmative Action, Anyway?

Affirmative action is “defined as a set of procedures designed to: eliminate unlawful discrimination among applicants, remedy the results of such prior discrimination, and prevent such discrimination in the future.” Cornell Law School, Legal Information Institute, Affirmative Action, https://www.law.Cornell.edu/Wex/affirmative_action (last visited July 3, 2023). So, right off the batt, I hope this definition helps dispel a lot of the confusion I’m seeing out there. Affirmative action, at its core, is simply action taken to prevent discrimination and rectify the impact of past discrimination. That second part: rectifying past discrimination will come up again later, so keep it in mind. That’s it. Now, over the years, we see that universities have turned this concept into actions which affirmatively favor folks based solely on one of those four factors, which has was subsequently prohibited in case precedent; but which is consistent with the initial intent of affirmative action—specifically rectifying past discriminatory admissions practices.

As we’ll see, rectifying past discriminatory action was seen as inconsistent with the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, and therefore prohibited. However, prohibiting universities from trying to rectify past discrimination did not mean that universities couldn’t consider race, creed, color or national origin.

In fact, that same precedent which didn’t like the second half of affirmative action encouraged consideration of race, creed, color and national origin because it resulted in a diverse student body, which in turn benefitted the overall education offered by the university.

Universities, however, were not permitted (following the two seminal cases on this matter, which will be discussed further below) to use race as the sole determining factor in considering whether to approve one candidate over another. In other words, when all other things are considered equal, someone shouldn’t get a leg up solely on the basis of race, creed, color or national origin. For example, if two students: one white and one black, have identical credentials (both went to the same high school; both have the exact same extracurriculars, leadership experience; work experience; grades; upbringing, etc.) the Black person cannot be favored over the White person or vice versa, simply by virtue of the color of their skin (I guess in that situation, you just admit both of them).

While the concept of affirmative action has been around in some form or another ever since we wrote our Constitution, it began to crystallize in the 50s and 60s with the Civil Rights Movement and President Kennedy. It was Kennedy who issued an executive order in 1961 mandating government contractors “take affirmative action to ensure that applicants are employed, and that employees are treated during employment, without regard to their race, creed, color or national origin.” Id. Since 1965, government contractors have been required to document their affirmative action programs through compliance reports.

Important reminder before continuing: our Constitution gives us rights and privileges ONLY against our government. It is essentially a social contract between us and the government whereby we have to do certain things as citizens (mostly pay taxes), and in return, the government can’t do certain things to us (like search our homes without due process, or prevent us from speaking freely). Now, obviously, there are exceptions when you’re talking about the commerce clause; but that’s for another blog.

So, when Kennedy issued that executive order for affirmative action, it could only apply to government contractors, government employees, and any institution which received government funding.

That’s why affirmative action applies to universities—most receive funding from the government.

A. Historical Precedent

The progenitor of the legal precedent involving affirmative action was Brown v. Board of Education, 374 U.S. 483 (1954). That’s right, kids. Brown was the first case to discuss affirmative action. Why? Remember: affirmative action was always a framework for preventing and remedying discrimination. The Constitution was colorblind and many would argue race, color, creed and national origin should simply be ignored in favor of the merit of each student’s personal achievements. Color blindness, while a laudable end goal (in terms of discrimination), is not practical. It is not practical, because it ignores the reality of the dynamics in this country and therefore cannot offer an actual real solution to systemic prejudice. But we’ll chat more about that later in the “My Fucking Opinion” section.

In Brown, the Supreme Court held that schools may not exclude minority students from white schools by sending the minority students to schools that separately service minority students. It was this case that overturned the concept of “separate but equal.” Separate but equal is not actually equal in the same way that colorblindness won’t actually fix the systemic prejudice.

The next seminal case on affirmative action holds one of the two spotlights in the 2023 Supreme Court’s ruling: Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978). In Bakke (pronounced “Back-ee”), the University of California reserved 16 spots in each entering class of 100 students for minority students. Bakke was mad because he got passed up for a minority student. As Roberts *hounds* in his opinion, there was no majority opinion in Bakke. (That means no one could agree on anything so everyone just came up with their own opinion). Justice Powell was not the Chief Justice, but his opinion nevertheless garnered the most analysis and support from other jurisdictions. Powell first examined whether a private right of action existed under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. He found there was and proceeded with his analysis of the Civil Rights Act:

The language of s. 601, 78 Stat. 252, like that of the Equal Protection Clause, is majestic in its sweep:

“No person in the United States shall, on the ground of race, color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

The concept of “discrimination,” like the phrase “equal protection of the laws,” is susceptible of varying interpretations, for, as Mr. Justice Holmes declared,

“[a] word is not a crystal, transparent and unchanged, it is the skin of a living thought, and may vary greatly in color and content according to the circumstances and the time in which it is used.”

Towne v. Eisner, 245 U.S. 418, 245 U.S. 425 (1918).

***

Examination of the voluminous legislative history of Title VI reveals a congressional intent to halt federal funding of entities that violate a prohibition of racial discrimination similar to that of the Constitution. Although isolated statements of various legislators, taken out of context, can be marshaled in support of the proposition that s. 601 enacted a purely color-blind scheme without regard to the reach of Equal Protection Clause, these comments must be read against the background of both the problem that Congress was addressing and the broader view of the statute that emerges from a full examination of the legislative debates.

What Powell is saying here is that words must be analyzed within the relevant context. The Civil Rights Act is seemingly colorblind, despite it having been enacted primarily to prevent discrimination against Black people. Powell continues:

The problem confronting Congress was discrimination against Negro citizens at the hands of recipients of federal moneys. Indeed, the color blindness pronouncements cited in the margin at n.19 generally occur in the midst of extended remarks dealing with the evils of segregation in federally funded programs. Over and over again, proponents of the bill detailed the plight of Negroes seeking equal treatment in such programs. There was simply no reason for Congress to consider the validity of hypothetical preferences that might be accorded minority citizens; the legislators were dealing with the real and pressing problem of how to guarantee those citizens equal treatment.

***

In view of the clear legislative intent, Title VI must be held to proscribe only those racial classifications that would violate the Equal Protection Clause or the Fifth Amendment.

So Powell has connected the Equal Protections Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 by saying the two were intended to reach the same goal. In so doing, he has also made an important point: words are the “skin of living thought,” and therefore vary greatly given the time and context in which they are used. Laws are made up of words. So what Powell is saying is that circumstances matter. This will become important when we discuss Roberts’ colorblind analysis.

Recall: Bakke is mad he wasn’t accepted to the University of California and sued. The university, in turn, argued its admissions process was constitutional. In order to determine whether the University’s admissions process was constitutional, the Court had to follow a certain analytical protocol. We call this the “standard of review,” and it is the framework courts use to examine things. Think of it like an IKEA instruction manual: if you want to put together a cabinet, you have to follow the cabinet instruction manual. If you want to put a bed together, you have to follow the bed instruction manual.

When courts are examining whether a law is discriminatory, or in this case, whether a governmentally-funded institution is being discriminatory in its admissions program, courts must use what’s called “Strict Scrutiny” to determine the constitutionality of that admissions program. In order to pass strict scrutiny, the university must be undertaking its admission program to “further a compelling governmental interest,” and must have narrowly tailored the program to achieve that interest. In other words, the University of California had to have had a good reason to reserve 16 of the 100 available spots in the class for minorities, AND, the program couldn’t be so broad as to have adverse effects on other groups. Powell did a good job of explaining what protocol the Court had to follow to examine the issues brought before it:

The parties…disagree as to the level of judicial scrutiny to be applied to the special admissions program.

***

The special admissions program is undeniably a classification based on race and ethnic background. To the extent that there existed a pool of at least minimally qualified minority applicants to fill the 16 special admissions seats, white applicants could compete only for 84 seats in the entering class, rather than the 100 open to minority applicants. Whether this limitation is described as a quota or a goal, it is a line drawn on the basis of race and ethnic status.

The guarantees of the Fourteenth Amendment extend to all persons. Its language is explicit: “No state shall…deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” It is settled beyond question that the “rights created by the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment are, by its term, guaranteed to the individual. The rights established are personal rights.”

Shelly v. Kraemer, supra at 334 U.S. 22…

The guarantee of equal protection cannot mean one thing when applied to one individual and something else when applied to a person of another color. If both are not accorded the same protection, then it’s not equal.

***

Racial and ethnic classifications…are subject to stringent examination without regard to…additional characteristics.

***

“Distinctions between citizens solely because of their ancestry are, by their very nature, odious to a free people whose institutions are founded upon the doctrine of equality.”

***

“[A]ll legal restrictions which curtail the civil rights of a single racial group are immediately suspect. That is not to say that all such restrictions are unconstitutional. It is to say that courts must subject them to the most rigid scrutiny.”

***

We have held that, in “order to justify the use of a suspect classification, a State must show that its purpose or interest is both constitutionally permissible and substantial, and that its use of the classification is ‘necessary…to the accomplishment’ of its purpose or the safeguarding of its interest.”

In re Griffiths, 413 U.S. 717, 413 U.S. 721-22 (1973) (Emphasis added).

The special admissions program purports to serve the purposes of (i) “reducing the historic deficit of traditionally disfavored minorities in medical schools and in the medical profession,”… (ii) countering the effects of societal discrimination;…(iii) increasing the number of physicians who will practice in communities currently underserved; and (iv) obtaining the educational benefits that flow from an ethnically diverse student body. It is necessary to decide which, if any, of these purposes is substantial enough to support the use of a suspect classification.

(Emphasis added).

***

The fourth goal asserted by petitioner is the attainment of a diverse student body. This clearly is a constitutionally permissible goal for an institution of higher education. Academic freedom, though not a specifically enumerated constitutional right, long has been viewed as a special concern of the First Amendment. The freedom of a university to make its own judgments as to education includes the selection of its student body. Mr. Justice Frankfurter summarized the “four essential freedoms” that constitute academic freedom:

***

…to determine for itself on academic grounds who may teach, what may be taught, how it shall be taught, and who may be admitted to study.

***

The Nation’s future depends upon leaders trained thought wide exposure to that robust exchange of ideas which discovers truth ‘out of a multitude of tongues, [rather] than through any kind of authoritative selection.’ United States v. Associated Press, 52 F.Supp. 362, 372.”

***

Physicians serve a heterogeneous population. An otherwise qualified medical student with a particular background—whether it be ethnic, geographic, culturally advantaged or disadvantaged—may bring to a professional school of medicine experiences, outlooks, and ideas that enrich the training of its student body and better equip its graduates to render with understanding their vital service to humanity.

Ethnic diversity, however, is only one element in a range of factors a university may properly consider in attaining the goal of a heterogeneous student body.

***

Respondent urges…that petitioner’s dual admissions program is a racial classification that impermissibly infringes his rights under the Fourteenth Amendment. As the interest of diversity is compelling in the context of a university’s admissions program, the question remains whether the program’s racial classification is necessary to promote this interest.

Powell found the University’s racial quotas were not a good way of achieving diversity. Importantly, however, Powell did not say the benefits which flow from student body diversity were immeasurable such that they were incapable of being examined under the strict scrutiny standard of review. Indeed, it was the benefits which flowed from a diverse student body that PASSED strict scrutiny. There was no further analysis as to whether the benefits also had to be measurable. Again—they already were. This is important, because Roberts seems to believe such benefits must be measurable in order to be examined under the strict scrutiny standard of review.

Now: remember when you read, like 5,000 pages ago, that there was no majority opinion in Bakke, and that it was just this wishy-washy amorphous globule of precedent that no one really knew what to do with? Well that all changed in 2003, when the Supreme Court heard the Grutter case.

The court in Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306 (2003) adopted Powell’s ruling that the educational benefits flowing from a diverse student body was a compelling government interest which could support classifications based on race, so long as the means by which the institution was using to attain that goal actually attained that goal. In Grutter, the University of Michigan Law School Admissions Office used race in its admissions process. The school used race as one of a number of factors; race could not automatically result in an acceptance or rejection. The court held that this plan was narrowly tailored enough to satisfy strict scrutiny because the “program is flexible enough to ensure that each applicant is evaluated as an individual and not in a way that makes race or ethnicity the defining feature of the application.” The court found that the law school “engage[d] in a highly individualized, holistic review of each applicant’s file, giving serious consideration to all the ways an applicant might contribute to a diverse educational environment.”

In dicta (which means, not authoritative. Kind of just like a musing), Justice O’Connor mentioned that “25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest approved today.” It is this non-authoritative dicta Roberts treats as authoritative in his opinion. Likely to stab at the two liberal judges dissenting.

Dick.

Anyway, that was a lot of words. So what’s the takeaway?

B. Takeaway

The takeaway is that federally-funded institutions can’t use race, color, creed or national origin as a sole determining factor in whether a student is accepted or rejected. If they’re going to consider race, creed, color or national origin, the institution has to do so in a holistic way which focuses on the individual. Roberts reaches this same conclusion; but in so doing, appears to also eviscerate the very thing Bakke and Grutter established as a permissible reason to utilize racial classification: educational benefits of diversity.

II. What the Fuck did Harvard and University of North Carolina Even DO

Roberts describes how Harvard’s admissions program works on page two of the majority opinion, relying on information provided by Harvard:

Every application is initially screened by a “first reader,” who assigns scores in six categories: academic, extracurricular, athletic, school, support, personal, and overall…A rating of “1” is the best; a rating of “6” is the worst…A score of “1” on the overall rating—a composite of five other ratings—“signifies an exceptional candidate with >90% chance of admission.”…In assigning the overall rating, the first readers “can and do take an applicant’s race into account.”

Once the first read process is complete, Harvard convenes admissions subcommittees…The subcommittees are responsible for making recommendations to the full admissions committee….The subcommittees can and do take an applicant’s race into account when making their recommendations.

The next step of the Harvard process is the full committee meeting…its discussion centers around the applicants who have been recommended by the regional subcommittees. At the beginning of the meeting, the committee discusses the relative breakdown of applicants by race. The “goal,” according to Harvard’s director of admissions, “is to make sure that [Harvard does] not hav[e] a dramatic drop-off” in minority admissions from the prior class…At the end of the full committee meeting, the racial composition of the pool of tentatively admitted students is disclosed to the committee. The final stage of Harvard’s process is called the “lop,” during which the list of tentatively admitted students is winnowed further to arrive at the final class. Any applicants that Harvard considers cutting at this stage are placed on a “lop list,” which contains only four pieces of information: legacy status, recruited athlete status, financial aid eligibility, and race…The full committee decides as a group which students to lop…In the Harvard admissions process, “race is a determinative tip for” a significant percentage “of all admitted African American and Hispanic applicants.”

So, Harvard definitely considers race, and if that quote was not taken out of context, it would appear Harvard considers race a determinative factor “for a significant percentage of African American and Hispanic applicants.”

To me, that means when all else is considered equal, Harvard will give the spot to the African American or Hispanic applicant. Now, this is where it becomes tricky and possibly creates a conflict between the original affirmative action executive order and subsequent case law.

Recall: part of that executive order required affirmative action to help cure the impacts of past discrimination. Yet, subsequent case law—Bakke and Grutter—say that remedying past discrimination isn’t sufficient to create a compelling state interest. Further, looking at this issue at a 10,000 foot view, you can’t balance the imbalance caused by systemic racism without doing what Harvard and UNC and several other universities are doing. We’ll get more to that later in the opinion section; but I want your brain primed before we get into the opinion. Judges and lawyers are a wiley folk. Our gift is very eloquently persuading you to walk off a bridge, so it’s easy to become lulled into one view or another. Stay objective, folks.

III. What the Fuck Does the Opinion ACTUALLY Say?

I’ll tell you what it doesn’t explicitly say. It doesn’t explicitly say affirmative action is now illegal. It doesn’t say that colleges can no longer consider race, color, creed or national origin at all when determining whether to accept an applicant.

Roberts is a fucking coward, though Thomas is always brazen enough to drop bombs: Bakke and Grutter are no more. While Roberts danced around the eventualities with his words, I think his intent was to create the legal framework for the eradication of consideration of these factors at all. In other words, Roberts is beginning to establish a colorblind legal framework. While this may sound nice; it is not.

Remember: context matters.

So, let’s dive in to what Roberts has to say. Roberts begins his analysis by dedicating several pages to both Bakke and Grutter. Importantly, nowhere in his analysis of these two cases does Roberts suggest they were improperly ruled upon; that they are distinguishable from the cases at hand; or that they should be overturned. Instead, he uses these cases to confirm that the educational benefits flowing from diversity are still compelling government interests justifying classifications based on race (so long as the means actually get you to the ends).

Nowhere in his analysis of these cases does Roberts say that the educational benefits flowing from diversity are fatally immeasurable such that they cannot be analyzed under strict scrutiny. Despite this, Roberts later in his opinion states the following:

First, the interests [Harvard and UNC] view are compelling cannot be subjected to meaningful judicial review. Harvard identifies the following educational benefits that it is pursuing.

Okay. Full fucking stop. Roberts acknowledges in one breath that educational benefits flowing from diversity collectively constitute a compelling government interest, while in the next, Roberts says that educational benefits can’t be measured and therefore can’t be examined under strict scrutiny. It’s like he’s saying a football that’s already been thrown through the field goal can’t get points because it was thrown too low through the field goal. Like, bitch? There were no rules about how high the ball had to be thrown—only that it makes it through the damn goal.

Powell never delineated between educational benefits in his 1978 ruling—he simply acknowledges they exist and as such are compelling. Therefore, educational benefits are a compelling government interest. They need not be individually scrutinized. Roberts nevertheless continues:

Although these are commendable goals, they are not sufficiently coherent for purposes of strict scrutiny. At the outset, it is unclear how courts are supposed to measure any of these goals.

This. This right here is what myself and the dissenters are worried about. It is this little paragraph in a 237-page opinion/dissent that can be used to undermine the rulings in Bakke and Grutter, which both allow consideration of race in admissions programs. After this, Roberts kind of ignores this conclusion and goes on with his analysis, focusing more on what Bakke and Grutter found were limitations on use of race-based affirmative action, ultimately ruling more or less consistently with Brown, Bakke and its progeny. The problem is if Roberts is now saying educational benefits cannot be examined under the strict scrutiny standard of review due to their ambiguity, he can’t also say that educational benefits can serve as a compelling governmental interest. Roberts nevertheless doubles down on Harvard’s proffered educational benefits:

Respondents’ second proffered end point fares no better. Respondents assert that universities will no longer need to engage in race-based admissions when, in their absence, students nevertheless receive the educational benefits of diversity. But as we have already explained, it is not clear how a court is suppose to determine when stereotypes have broken down or “productive citizens and leaders” have been created. 567 F.Supp. 3d, at 656. Nor is there any way to know whether those goals would adequately be met in the absence of a race-based admissions program. As UNC itself acknowledges, these “qualitative standard[s]” are “difficult to measure.”

Here is where Roberts says educational benefits Bakke and Grutter both found were compelling governmental interests are no longer viable compelling interest because they are immeasurable:

For the reasons stated above, the Harvard and UNC admissions programs cannot be reconciled with the guarantees of the Equal Protection Clause. Both programs lack sufficiently focused and measurable objectives warranting the use of race, unavoidably employ race in a negative manner, involve racial stereotyping, and lack meaningful end points. We have never permitted admissions programs to work in that way, and we will not do so today.

Roberts is tripling down here. Without explicitly overturning Bakke and Grutter, he one-hundo is. Now, because Roberts is an insufferable pussy, he tries to appeal to the anti-Nazi crowd:

At the same time, as all parties agree, nothing in this opinion should be construed as prohibiting universities from considering an applicant’s discussion of how race affected his or her life, be it through discrimination, inspiration, or otherwise.

Roberts then spends an inordinate amount of page-space and energy attacking the dissent. This is usually a sign that the majority is infirm in its ruling. They feel they need to defend it.

Listen: this goes for everything in life. If you feel the need to fervently defend your position against someone, it usually means you know you’re wrong. It’s why folks who are gay and not prepared to face that reality are the loudest proponents of anti-LGBTQIA everything.

Anywho; that’s enough of my opinion. Let’s taco-bout the dissent.

III. The Savage Dissent

I admit: I’m liberal. BUT, I also must take the other side’s argument hella seriously. To be a good lawyer, you can’t ignore the other side. You must take them seriously. It’s a trope that has persevered throughout the ages: NEVER. UNDERESTIMATE. YOUR OPPONENT.

So. I take both the majority and dissent very seriously.

Sotomayor is P.I.S.S.E.D.:

The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment enshrines a guarantee of racial equality. The Court long ago concluded that this guarantee can be enforced through race-conscious means in a society that is not, and has never been, colorblind.

***

[The Majority] holds that race can no longer be used in a limited way in college admissions to achieve such critical benefits. In so holding, the Court cements a superficial rule of colorblindness as a constitutional principle in an endemically segregated society where race has always mattered and continues.

This. This is the crux. Roberts and his majority are and have historically always been colorblind, including Justice Thomas, which is absurd to me. The definition, I suppose, of a “pick-me” person. Like, “Please, ya’ll white folk! I want to be you! I don’t want to be black! Pick Meeeeee!”

How embarrassing.

Anyway, Sotomayor continues:

If there was a Member if this Court who understood the Brown litigation, it was Justice Thergood Marshall, who “led the litigation campaign” to dismantle segregation as a civil rights lawyer and “rejected the hollow race-ignorant conception of equal protection” endorsed by the Court’s ruling today. Brief for NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (which brief, by the way was not cited ONCE in Roberts’ opinion. To be a good and effective lawyer, you NEED to take the opposing argument BY THE GOTDAMNED HORNS and dismantle it. Roberts failed to do so here). Justice Marshall joined the Bakke plurality and “applaud[ed] the judgment of the Court that a university may consider race in its admission process.”

***

Since Bakke, the Court has reaffirmed numerous times the constitutionality of limited race-conscious college admissions. First, in Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306 (2003), a majority of the Court endorsed the Bakke plurality’s “view that student body diversity is a compelling state interest that can justify the use of race in university admissions,” 539 U.S. at 325, and held that race may be used in a narrowly tailored manner to achieve this interest.”

Sotomayor is very clearly and concisely setting forth the establish legal precedent and how Roberts’ opinion is dismantling that long-established precedent. Now…dismantling long-established precedent is not always a bad thing. Think Plessy v. Ferguson, which incorrectly found that “separate but equa.l” was a thing that existed. It doesn’t.

And if you still think “separate but equal” is viable, I genuinely hope you kill yourself.

But I digress.

Sotomayor continues:

Bakke, Grutter, and Fisher are an extension of Brown’s legacy. Those decisions recognize that “experience lend[s] support to the view that the contribution of diversity is substantial.”

***

Racially integrated schools improve cross-racial understanding, “break down racial stereotypes,” and ensure that students obtain “the skills needed in today’s increasingly global marketplace…through exposure to widely diverse people, cultures, ideas, and viewpoints.

***

This compelling interest in student body diversity is grounded not only in the Court’s equal protection jurisprudence but also in principles of “academic freedom,” which “‘long [have] been viewed as a special concern of the First Amendment…In light of “the important purpose of public education and the expansive freedoms of speech and thought associated with the university environment,” this Court’s precedents recognize the imperative nature of diverse student bodies on American college campuses.”

***

[L]earning how to tolerate diverse expressive activities has always been ‘part of learning how to live in a pluralistic society” under our constitutional tradition. Kennedy v. Bremerton School District., 597 U.S. __,__ (2022)(slip op., at 29); cf. Khorrami v. Arizona, 598 U.S. __, __ (2022)(GORSUCH,J., Dissenting from denial of certiorari)(slip op., at 8)(collecting research showing that larger juries are more likely to be racially diverse and “deliberate longer, recall information better, and pay greater attention to dissenting voices”).

In short, for more than four decades it has been this Court’s settled law that the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment authorizes a limited use of race in college admissions in service of the educational benefits that flow from a diverse student body.

Then, Sotomayor hits the nail on the specific head that needs to be hit:

Today, the Court concludes that indifference to race is the only constitutionally permissible means to achieve racial equality in college admissions. That interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment is not only contrary to precedent and the entire teachings of our history…but is also grounded in the illusion that racial inequality was a problem of a different generation. Entrenched racial inequality remains a reality today.

***

That is true for society writ (sic) large and, more specifically, for Harvard and the University of North Carolina (UNC), two institutions with a long history of racial exclusion. Ignoring race will not equalize a society that is racially unequal. What was true in the 1860s, and again in 1954, is true today: Equality requires acknowledgment of inequality.

This is akin to that old (is it old? IDK at this point) adage, “you can’t get better unless you know there’s a problem,” or something like that. You can’t fix the problem until you acknowledge there’s a problem. Sotomayor acknowledged the problem and goes into great detail discussing the problem, which I will cover in the opinion section. After this, she begins to wrap up:

The Court today stands in the way of respondents’ commendable undertaking and entrenches racial inequality in higher education. The majority opinion does so by turning a blind eye to these truths and overruling decades of precedent, “content for now to disguise” its ruling as an application of “established law and move on.” Kennedy, 597 U.S., at__ (SOTOMAYOR, J., Dissenting) (slip op., at 29). As JUSTICE THOMAS puts is, “Grutter is, for all intents and purposes, overruled.” Ante, at 58.

It is a disturbing feature of today’s decision that the Court does not event attempt to make the extraordinary showing required by stare decisis. The Court simply moves the goalposts, upsetting settled expectations and throwing admissions programs nationwide into turmoil.

What Sotomayor is saying is Brown and its progeny long established that diversity and the benefits flowing therefrom DO constitute a compelling government interest. And what the Majority is doing here is upending that long-established precedent by saying it cannot even be examined, due to its ambiguity, much less ruled upon.

Answering the question whether Harvard’s and UNC’s policies survive strict scrutiny under settled law is straight-forward, both because of the narrow scope of the issues presented by petitioner…

The Court granted certiorari on three questions: (1) whether the Court should overrule Bakke, Grutter, and Fisher; or, alternatively, (2) whether UNC’s admissions program is narrowly tailored, and (3) whether Harvard’s admissions program is narrowly tailored.

***

Answering the last two questions, which call for application of settled law to the facts of these cases, is simple: Deferring to the lower courts’ careful findings of facts and credibility determinations, Harvard’s and UNC’s policies are narrowly tailored.

Sotomayor goes on to further establish how easy it would have been to reach a determination in light of the long-standing case law.

She finishes strong:

The Court concludes that Harvard’s and UNC’s policies are unconstitutional because they serve objections that are insufficiently measurable, employ racial categories that are imprecise and over broad, rely on racial stereotypes and disadvantage non minority groups, and do not have an end point…In reaching this conclusion, the Court claims those supposed issues with respondents’ programs render the programs insufficiently “narrow” under the strict scrutiny framework that the Court’s precedents command….In reality, however, “the Court today cuts through the kudzu” and overrules its “higher education precedents” following Bakke.

There is no better evidence that the Court is overruling the Court’s precedents than those precedents themselves. “Every one of the arguments made by the majority can be found in the dissenting opinions filed in [the] cases” the majority now overrules.

***

Lost arguments are not grounds to overrule a case. When proponents of those arguments, greater now in number on the Court, return to fight old battles anew, it betrays an unrestrained disregard for precedent. It fosters the People’s suspicions that “bedrock principles are founded…in the proclivities of individuals” on this Court, not in the law, and it degrades “the integrity of our constitutional system of government.” Vasquez v. Hillery, 474 U.S. 254, 265 (1986).

***

There is no basis for overruling Bakke, Grutter, and Fisher. The Court’s precedents were correctly decided, the opinion today is not workable and creates serious equal protection problems, important reliance interests favor respondents, and there are no legal or factual developments favoring the Court’s reckless course.

***

At bottom, six unelected members of today’s majority upend the status quo based on their policy preferences about what race in American should be like, but is not, and their preferences for a veneer of colorblindness in a society where race has always mattered and continues to matter in fact and in law.

. . .

Oof.

IV. BUT WHAT DOES IT ALL MEEEEAAAANNN

Great question. Even though I think originalism is the STUPIDEST theory aside from flat-earthers, I admit when you are interpreting a law, you gotta start with that law. You gotta start with the legislative intent of that law—the “spirit of the law,” if you will. Why? Because laws are enacted for reasons, and you have to understand what that reason was if you’re going to continue to uphold the law, or strike the law down. You need to know the reason the law was enacted to understand whether it applies to a certain set of facts. And—here’s why I think originalism is dumb— you have to consider that original reason WITHIN THE CONTEXT OF THE PRESENT DAY.

Like, you can’t look at a 1779 rule and apply it in 2023 in the same context. THEY ALL HAD LICE BACK THEN WHICH THEY COVERED WITH WIGS BECAUSE THEY DIDN’T KNOW HOW TO GET RID OF LICE.

So yeah. Context matters. And I continue to digress.

You need to look at the original rule and the original reasoning behind the rule. The original executive order Kennedy passed was to “take affirmative action to ensure that applicants are employed, and that employees are treated during employment, without regard to race, creed, color, or national origin.” The legislative intent behind this rule—remember, this was in the 60s—was to ensure that Black people were not being turned away from government positions, or government-affiliated positions simply because they were black (all else considered equal). Read in the context of today, it is easy to mold that rule into complete colorblindness. Thus, subsequent precedent and codification sought to better tailor Kennedy’s executive order.

Pursuant to 34 C.F.R. S. 100.3(6)(ii), educational institutions which have acted discriminatorily in the past MUST take affirmative action as a remedy.

They must.

Now, I suppose there is an argument that switching from actively denying minority applicants to becoming completely colorblind is a remedy of sorts, right? You’re no longer discriminating, but you’re also not really remedying anything. And I don’t think you can argue going from considering race to not considering race is “affirmative action.” I think ceasing to consider race is an omission.

But why isn’t just going completely colorblind a remedy?

Well…let’s look at the definition of “remedy:”

“Something that corrects or counteracts.”

Or

“The legal means to recover a right or to prevent or obtain redress for a wrong.”

Simply stopping a bad practice won’t correct the fall-out from that practice. And while in the simplest of circumstances, stopping a bad practice will at least prevent future harms caused by that bad practice, that is not the case for racism in this country. Simply not considering race is not going to get more minority students in Ivy League schools. You have to fix a whole lot of other stuff first before that starts working.

Back to the law. Think about it: remedies are why the legal system exists. It’s what my job is to secure. The legal system’s job is two-fold: (1) prevent future wrongs by punishing the wrong-doer and (2) put the person who was harmed back in or as close to the position they were in before the wrong occurred. Don’t believe me? Look it up.

Seriously. Look up the elements of damage for contracts and torts—the two most prevalent areas of dispute under the law. The elements for damages for these are to place the injured person in as close to the position they would have been in had the harm never happened.

You can’t really do that with Black people in this country by simply not being racist anymore. Our very cultural infrastructure is racist. If universities stopped considering race, the vast majority of the student population would by white or Asian. Why? Because Black and Hispanic people historically have less access to (1) stable homes; (2) money; and (3) quality education. Do you know how fucking hard it is to focus when you have to run for cover during a drive-by? Or when your parents beat you? Or when you haven’t eaten in over 12 hours because your mom doesn’t have enough money for food AND rent?

Yeah.

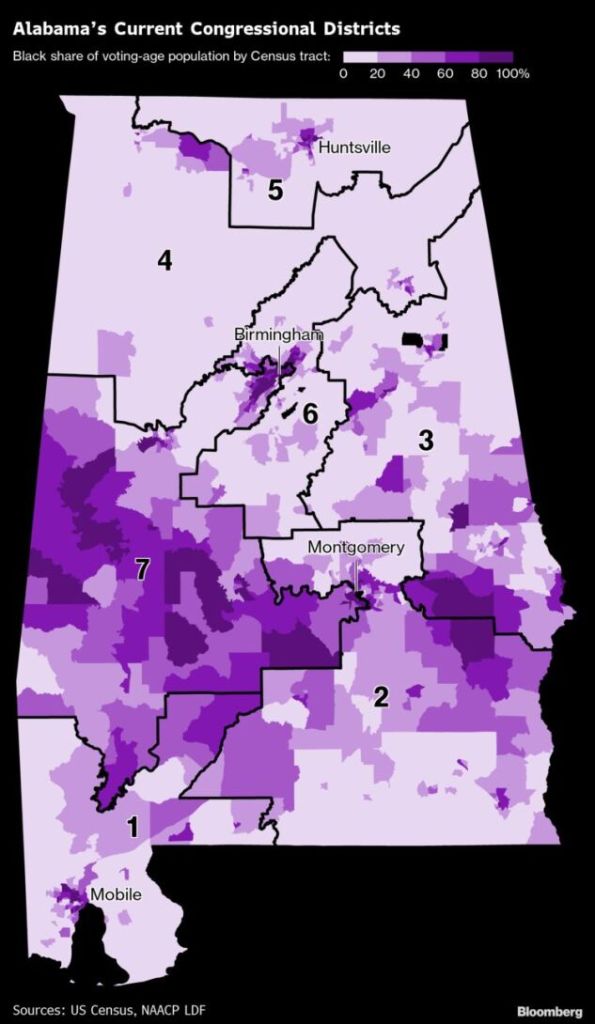

And what about those districts that don’t get funding for infrastructure? Why do you think that is? Why do you think politicians have such hard-ons for drawing district lines? They want to favor those areas who have the most amount of their constituents. Funding for a new baseball stadium in a rich white district instead of fixing the pothole-ridden road in the poor mostly Hispanic district? You got it. Defunding education in a poor mostly Black district in favor of paying for a new gymnasium at a primarily white school in a wealthier area of town? Yep.

I shit you not; but as always, I encourage you to do your own research. I did.

And I found a pretty cool article from the Brookings Institute discussing what exactly happens when educational institutions stop considering race in admissions:

[Adriana] Pita: …Here with us today…is Katherine Meyer, a fellow with the Brown Center on Education Policy here at Brookings.

***

Pita: …[W]e’ve seen a handful of other states previously ban affirmative action at their state level, California being one of the largest. What does their example show about what happens to racial diversity when systematic, race-conscious admissions aren’t permitted?

Meyer: That’s right. California is certainly the largest state to have banned the consideration of race in college admissions, but up to nine states at various points have had affirmative action bans regarding race to this point. So we have a good body of evidence about what happens to underrepresented student enrollment. And in specific cases like California, but also pooling across all of these states, we see that enrollment of Black, Hispanic, and Native students drops significantly, immediately. In California, it was around a 30 to a 40 percent drop in Black and Hispanic enrollment after the selective institutions were no longer able to consider race.

***

Pita: One of them statistics that’s been being cited today in a lot of stories around this is from a 2019 study of Harvard students that found that 43% of the white student body there were wither legacy admissions, recruited specifically for athletics, or that they were the relatives of staff or donors. And I was struck, Michelle Obama put out a very powerful statement today. And in it, she said, “so often we just accept that money, power, and privilege are perfectly justifiable forms of affirmative action.” What are we seeing in terms of any of these more selective schools thinking about rolling back some of these preferential policies like legacies and how effective would that be at helping to more balance the levels there?

Meyer: I think it’s such an important point that Michelle Obama made, that affirmative action is an umbrella term that can be used to describe any number of admissions policies. That today the Supreme Court didn’t ban affirmative action, they banned race-based affirmative action and race-conscious admissions. And things like legacy preferences or targeted athletic recruitment or engaging in early admissions policies are forms of affirmative action, they’re just forms of affirmative action that disproportionately benefit white students. And so I think we can expect to see a number of highly selective colleges in the coming weeks announce that they are going to eliminate legacy preferences. It has always been a dubious argument for why some students should get a tip in the admissions decision, but I imagine there’s been such a groundswell of advocacy around this, particularly from student groups at highly selective institutions pushing the institutions to eliminate this practice.

How will the Supreme Court’s Ruling Affect College Admissions?

So we know that the lack of race-based affirmative action in educational institution most definitely has a measurable impact on the percentages of minority students enrolled. But why?

Is it because minority students are lazy?

No. Shut the fuck up with that drivel and either get the fuck off my blog, or continue reading to learn something, sheeeeeeeeeee-at.

Sotomayor touched on why the percentage of minorities admitted to Ivy League schools has always been low:

Today, the Court concludes that indifference to race is the only constitutionally permissible means to achieve racial equality in college admissions. That interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment is not only contrary to precedent and the entire teachings of our history, but is also grounded in the illusion that racial inequality was a problem of a different generation. Entrenched racial inequality remains a reality today. That is true for society writ (sic) large and, more specifically, for Harvard and [UNC], two institutions with a long history of racial exclusion.

Ignoring race will not equalize a society that is racially unequal. What was true in the 1860s, and again in 1954, is true today: Equality requires acknowledgment of inequality.

After more than a century of government policies enforcing racial segregation by law, society remains highly segregated. About half of all Latino and Black students attend a racially homogenous school with at least 75% minority student enrollment . The share of intensely segregated minority schools (i.e., schools that enroll 90% to 100% racial minorities) has sharply increased. To this day, the U.S. Department of Justice continues to enter into desegregation decrees with schools that have failed to “eliminat[e] the vestiges of de jure segregation.”

Moreover, underrepresented minority students are more likely to live in poverty and attend schools with a high concentration of poverty. When combined with residential segregation and school funding systems that rely heavily on local property taxes, this leads to racial minority students attending schools with fewer resources. In turn, underrepresented minorities are more likely to attend schools with less qualified teachers, less challenging curriculum, lower standardized test scores, and fewer extracurricular activities and advanced placement courses. It is thus unsurprising that there are achievement gaps along racial lines, even after controlling for income differences.

Sotomayor goes on and on with more and more statistics, touching upon disproportionate disciplinary actions taken against Black students; how minority students are less likely to have parents familiar with the admissions process (that is a HUGE one); no money for extracurriculars, etc. This is why simply ceasing to consider race is not going to achieve the legislative intent of affirmative action. You have to affirmatively cure what centuries of racism has caused.

Neat, huh? That you need to actually do the thing that the law is named after?

Anyway, I’m going to end Sotomayor’s take with a quote she includes in her dissent:

“Because talent lives everywhere, but opportunity does not, there are undoubtedly talented students with great academic potential who have simply not had the opportunity to attain the traditional indicia of merit that provide a competitive edge in the admissions process.”

Brief for Harvard Student and Alumni Organizations as Amicus Curiae 16.

So. We have now established what affirmative action is; why it’s important; and the actual real-world consequences of not having it.

What the Court has done, without explicitly saying so, is prohibited the consideration of race as a factor for admissions by ruling that the educational benefits which flow from diversity are so vague and immeasurable that they cannot survive the strict scrutiny standard of review.

In so ruling, the Court has practically overruled both Bakke and Grutter, which both found that the benefits which flow from diversity are not only sufficiently measurable; but do in fact constitute compelling government interests.

Since the educational benefits flowing from diversity was held to be the only sufficient reason for admissions programs to consider race among those provided by the universities being sued, there is no other legal foundation for allowing universities to consider race at all other than extrapolating justification from 34 C.F.R. S. 100.3(6)(ii), which requires universities which have acted discriminatorily in the past take affirmative action as a remedy. You can’t really remedy past discrimination without considering race in your admissions program. How the fuck else are you going to determine if you’re actually “remedying” anything?

So the main takeaway here? Race-based affirmative action is essentially kaput. Aside from a minority student including how race impacted their personal journey in an essay and the university being super impressed with it, race can no longer be a factor, much less a determining factor, in admitting students. Hopefully, universities desirous of maintaining diversity will eliminate other forms of affirmative action which disproportionately benefit white folks to help re-balance the scales…but my guess is with all the shit a lot of minority students have to deal with still being a thing, we’re going to see what happened in California happen across the U.S.

And here’s the sad part: getting that higher education at these Ivy League schools will almost 100% of the time get you a damn good job. That damn good job is going to pay you a lot of money, and you get to use that money to get you and your family into a better social position. So, it was this access to higher education that was actually HELPING all that other shit. And they did that WITHOUT other government action (like, I don’t know, funding education at the K-12 levels; infrastructure; etc).

So yeah. Fuck this Court.